Cloud & Backend EP 4 - Infrastructure as Code Landscape

How to categorize IaC tools?

Hello and welcome to a new edition of the Progressive Coder newsletter.

The topic for today - Infrastructure as Code landscape

IaC started off with the commoditization of virtual machines sometime around the mid-2000s.

As with many things in the cloud infra space, Amazon played a key role in making IaC popular. The launch of AWS Cloudformation in 2009 made IaC an essential DevOps practice.

But what makes IaC such a conversation-inspiring topic these days?

Probably, the below sentiment.

Yes, IaC lets you treat your infrastructure just like your application code.

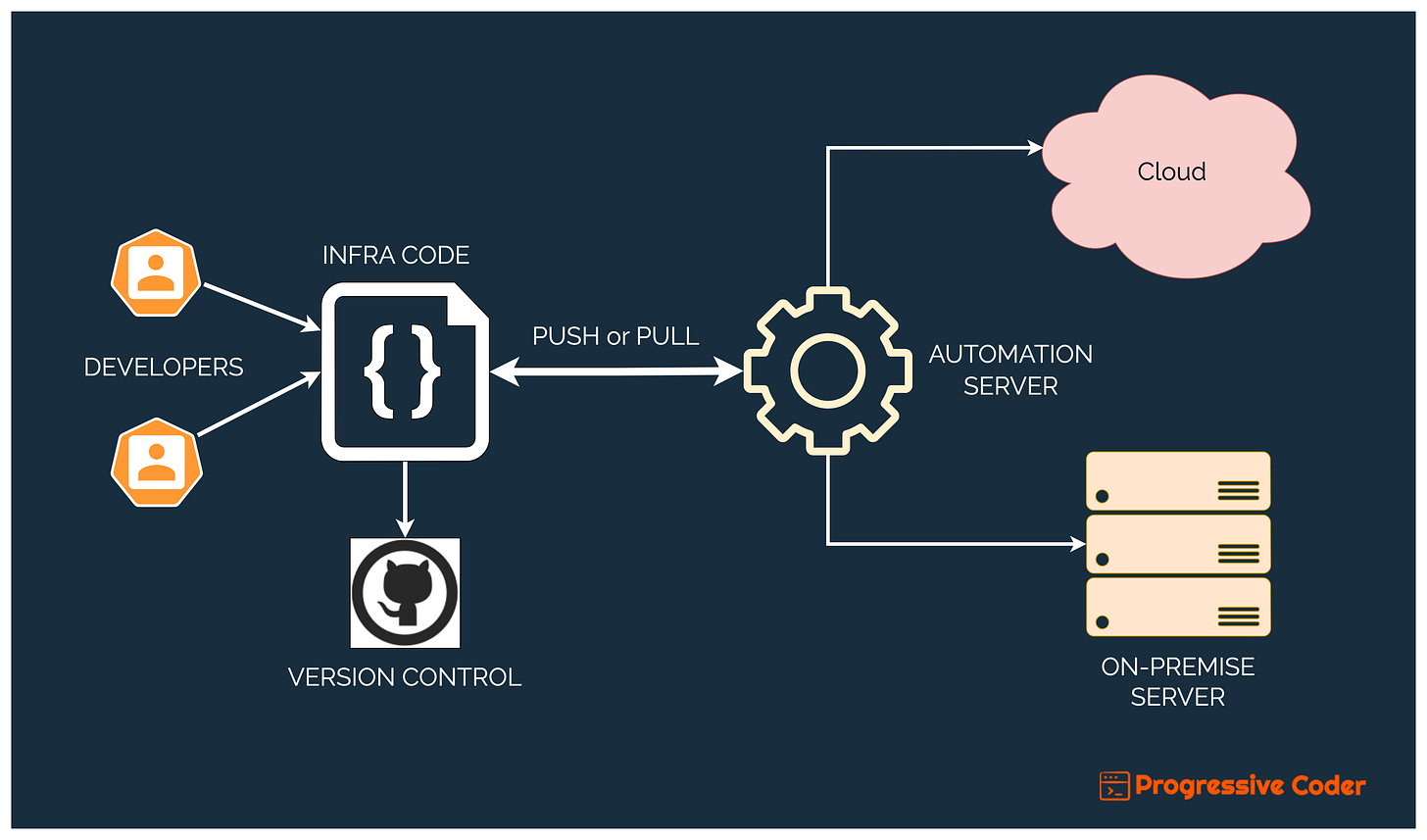

Here’s what things look like from a big-picture point of view, no matter the tool you use.

Developers define and write the infrastructure code and put it in a version control tool like GitHub.

This code goes through the pull request and peer-review magic, ultimately ending up in a release branch.

After that, the IaC tool takes over and creates the infrastructure in the cloud or on-premise.

With IaC, you are no longer dependent on a secret society of extremely important engineers, who own the keys to the application’s infrastructure.

With IaC, you can write and test code that makes creating, updating and deleting infrastructure a matter of pushing a button.

But the IaC landscape is daunting. Even though the industry is still nascent, there must be hundreds of tools out there. And more are coming.

In this post, I cut through the clutter and divide the IaC landscape into broad categories that can help you make a more informed choice.

How to think about IaC Tools?

The problem with IaC tools is that there are so many of them. Also, each one of them is marketed as the best out there.

This makes it tough for developers to understand and select the right tools for their requirements.

To begin with, stop looking at these tools in isolation.

Instead, look at them based on 3 broad categories.

👉 Based on the Language

The first wave of IaC tools relied on a Domain-Specific Language or DSL to describe the infrastructure.

Tools such as Ansible, Terraform & Chef fall under the DSL category.

For example, Terraform uses a special language known as Hashicorp Configuration Language (HCL) to describe the resources.

Here’s an example to define an EC2 instance in Terraform using HCL:

provider "aws" {

region = "us-west-2"

profile = "terraform-user"

}

resource "aws_instance" "hello_aws" {

ami = "ami-0ceecbb0f30a902a6"

instance_type = "t2.micro"

tags = {

Name = "HelloAWS"

}

}On the other end of the spectrum, we have IaC tools that use existing programming languages to describe the infrastructure.

Tools such as Pulumi & AWS CDK fall into this category.

Here’s how the EC2 code is written for Pulumi with TypeScript.

import * as pulumi from "@pulumi/pulumi";

import * as aws from "@pulumi/aws";

const instance = new aws.ec2.Instance("my-ec2-instance", {

ami: "ami-0c55b159cbfafe1f0", // Amazon Linux 2 AMI

instanceType: "t2.micro",

tags: {

Name: "HelloAWS",

},

});

export const publicIp = instance.publicIp;For reference, Pulumi supports a bunch of languages such as TypeScript, Python, Go, C#, Java and even YAML.

🚀 What’s the takeaway?

If you don’t want to learn a new domain-specific language for writing infra code, go for an IaC tool that works with a familiar language.

This is particularly useful for teams that don’t have a dedicated DevOps role and rely on application developers to dabble with infrastructure. If you are a team lead, you can make things easy for them by going with a tool that supports a familiar programming language.

👉 Based on the Approach

You can also differentiate IaC tools on the basis of their provisioning approach - push and pull.

Push-based tools use a centralized server to push configuration changes to target machines. For example, Ansible & Terraform Enterprise.

Pull-based tools use a centralized server to store configuration information and rely on agents on the target machines to pull the latest configuration from the server. For example, Puppet & Chef.

Here’s a diagram that illustrates the difference between these two approaches in the context of Ansible and Puppet.

In Ansible, a central node uses SSH to connect to host systems and configures them.

In Puppet, an agent installed on the host system pulls the manifest from the Puppet master and applies the configuration on the machine.

🚀 What’s the takeaway?

If you don’t want to install additional software on your host machines, go for a tool that supports a push-based approach.

However, if you want things to be more automated, pull-based tools shine as your host machines are automatically configured as soon as they are ready.

👉 Based on the Philosophy

Lastly, you can also group IaC tools based on their philosophy - declarative and imperative.

Declarative IaC is like setting a destination in your GPS and letting the tool figure out the best route to get you there.

You simply declare the desired state of your infrastructure and let the IaC tool do the rest. Tools like Terraform & AWS Cloudformation follow this philosophy.

Here’s what a declarative code looks like in Terraform:

resource "aws_instance" "hello_aws" {

ami = "ami-0c55b159cbfafe1f0"

instance_type = "t2.micro"

tags = {

Name = "HelloAWS"

}

}Imperative IaC is all about giving instructions to the IaC tool on how to reach the destination.

You have to describe the exact steps needed to reach the desired state of the infrastructure. Tools like Ansible & Puppet follow this philosophy.

Here’s what imperative code looks like in Ansible:

- name: Install Apache

apt:

name: apache2

state: present

- name: Configure Apache

template:

src: /path/to/httpd.conf.j2

dest: /etc/httpd/conf/httpd.conf

mode: '0644'🚀 What’s the takeaway?

If you want to make your IaC code easy to write and reason about, go for a tool that supports declarative philosophy.

However, if you want flexibility, go for imperative tools.

👉 Over to you

Are you planning to use IaC in your project?

Also, which type of IaC tool do you find more preferable?

DSL or non-DSL

Push or Pull

Declarative or Imperative

Write your replies in the comments section.

If you found today’s post useful, consider sharing it with friends and colleagues.

And here’s an uncanny observation I had while writing this post: